Six months ago, I returned to my hometown. My lease in New York City had expired, and while I had made significant progress with PTSD, the clamor and stress of the city had become too much for me. I needed somewhere quieter, somewhere familiar. It seemed like a counterintuitive move, given the bad things that had happened to me there. Then I saw a rental listing: a house three doors down from where I grew up.

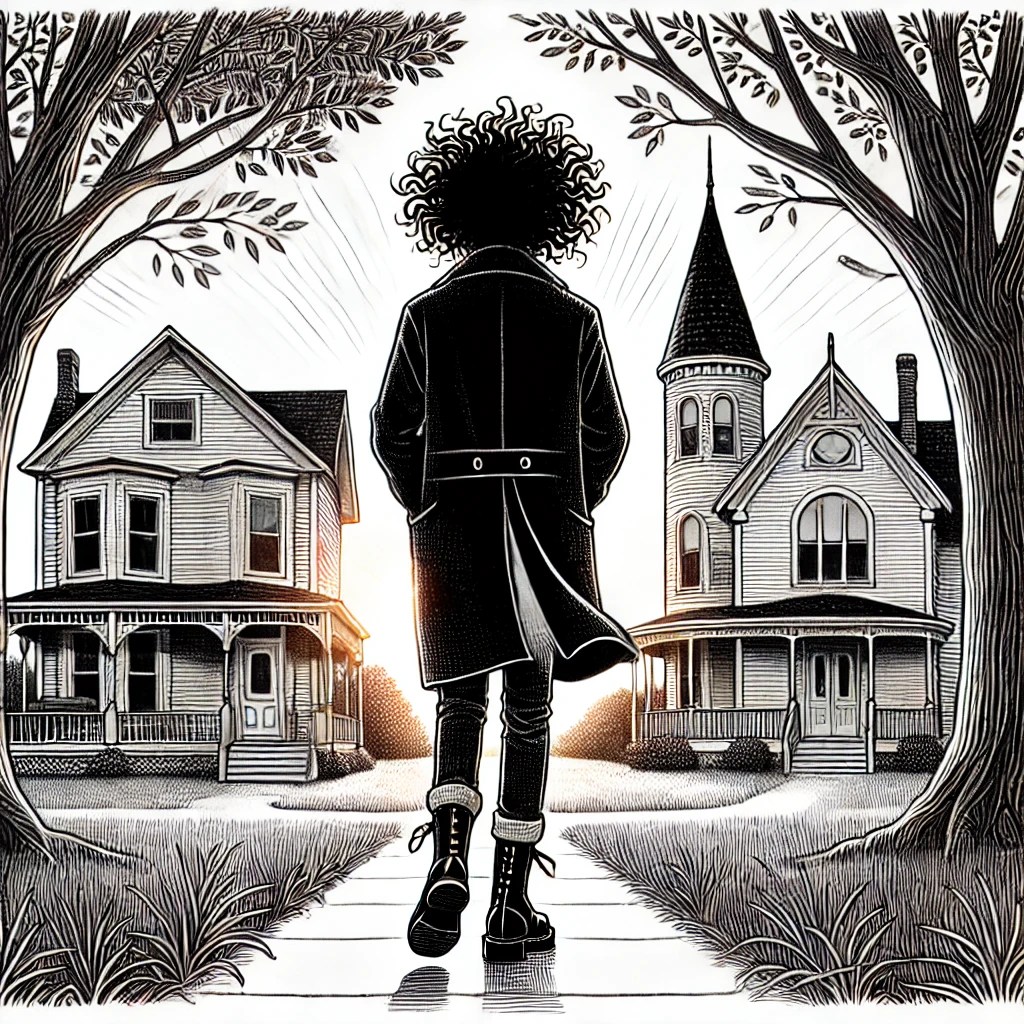

It felt less like a decision and more like a gravitational pull. I didn’t move home with a sense of relief or nostalgia. I came back filled with anger—anger at the life I’d lived, at the people who had failed me, at the systems that had allowed harm to flourish. I told myself I was here to confront the ghosts of my past. To kick over every stone and bring it all into the light.

I even had a plan. I was going to write a book—an exhaustive catalog of every horror I had endured and every perpetrator who had hurt me. I imagined it as a reckoning, a way to force accountability on a world that had long since moved on.

At the time, I thought that writing about my trauma would help me—that documenting every detail and naming every perpetrator would give me the closure I was chasing. But something about being back in this place started to shift my perspective.

Where the Pines Grow Wild

The person who caused the greatest harm in my life was my age when he decided to do this to me. He made that decision not out of malice but out of desperation. He needed money. He was compromised, easily blackmailed. At first, this knowledge only deepened my fury—not just at him, but at the banality of the circumstances that allowed such evil to take root.

But as the weeks passed, something began to change.

Instead of feeling haunted, I found myself soothed by the familiarity and natural beauty of this place. Walking the same hills and valleys, enjoying the small Victorian architecture, sitting in the same parks, and seeing the same trees I had grown up around, I began to reconnect with a part of myself that I had thought was lost forever.

Rustling Through the Trees

The man who hurt me, a kind of father figure, lived in a grand Detroit bungalow. When I was a kid, I used to dream about growing up, buying it, and living there with all of my childhood friends and as many animals as we could cram into the place. Once I was back in my hometown, I began to drive by this old house at least once a week. One day, as I was driving by slowly, I noticed that the current owner was in the driveway. He was the same man who bought the house from the perpetrator.

I mentioned that his house had been a home-away-from-home. I described swimming in the pool and playing dress-up in the attic. I did not tell him about the bad things that happened there.

After a few minutes of conversation, the man invited me inside for a tour. His wife, who was in the front yard playing with her grandchildren, insisted. I felt the same counterintuitive gravitational pull that had guided me to my childhood home.

Pounding Down that Broken Path

The house felt warm and full of love. The couple had put a lot of work into the large home, uncovering the white maple floors and trim. In creating a sanctuary for their children and grandchildren, they had exorcised any evil that had once lived there.

I was surprised at how easy it was to connect to the happy memories I had in that house. I could remember the bad things, but those events were squarely in the past. The happy memories were alive, vibrant, and within reach.

I began to realize that my move home was not about confronting the past but an opportunity to rediscover love in all its forms.

I felt the same easy access to happiness and love in my rental house. The love I felt from my father when I was a little kid, just a few doors from where I live now, has become palpable. Sometimes, when I am still, it feels like he is wrapping me in a blanket of love. I can even feel my shoulders tingle, like they do when someone hugs you. It is so obvious now that the love he gave me when I was little, and when he was young and full of potential, established an unshakable framework that sustained me through everything that followed.

I have also rediscovered other loves that I enjoyed in my childhood. The love of my first boyfriend, a transformative experience, is another gift I explored more fully since moving home. That love, raw and innocent, taught me something about myself that I’m only now fully coming to understand.

I’ve also rediscovered neighborly love. When I was little, my neighbor Sally would always bring me little gifts, like notepads and pens. At the holidays, she would embroider stockings with my name and fill them with candy on my front porch. Now, my current neighbor, who lives in Sally’s old house, brought me a pie when I moved in. On Christmas, she left a mug with graham crackers at my front door. These small acts of kindness remind me that community can be the source of a smaller, quotidian love that provides an indelible sense of security and belonging.

There is also love I have rediscovered with old friends, people I have known since preschool. Spending time with them—visiting The Winery or sharing a quiet brunch in their homes—feels like reclaiming a long-lost part of myself. It is not nostalgia; it is the reintegration of a love that had always existed but that I was not fully able to embrace until now.

These forms of love—familial, romantic, neighborly, and platonic—are all pieces of the same puzzle. They were always there, even when I couldn’t see them clearly. And now, for the first time, I feel like I’m able to hold them, live in them, and let them shape the life I’m building.

Devil Snappin’ At My Heels

Three months before he died, the parish priest began visiting the man who had harmed me. They engaged in the sacrament of confession every day. At the time, I thought it was strange. At age 18, I didn’t understand why the priest was there so often or what they could possibly be discussing. I had not yet remembered the abuse.

Years later, as the memories surfaced, and as I began to recover, I put the pieces together. He wasn’t just confessing his actions—he was grappling with them, trying to reconcile the irreconcilable. He wasn’t a complete psychopath, devoid of humanity. He was a deeply compromised person, torn by conflict, who had loved me in his way and harmed me in ways that cannot be excused.

His life’s work, in the end, became the attempt to reconcile those two truths: his capacity for love and the enormity of the harm he caused.

Shining Hard and Bright

For years, my anger was overwhelming. I saw the violence I had experienced as a cruel mark, a burden that separated me from others. But as I began to reflect—walking and driving on my old streets, sitting in the same parks—I realized that the depth of violence I’d known had given me something unexpected.

When you know violence intimately, and it doesn’t destroy you, it deepens the way you understand and experience love, joy, respect, and integrity. They are no longer abstract concepts or fleeting feelings. They become profound, tangible, and accessible truths. Because I had known harm so deeply, I could experience these gifts in a way that felt sharper, richer, more real.

It was this realization—that the contrast itself was a gift—that began to shift my perspective.

I never wrote the book. I realized that writing about the trauma, or even speaking about it at length, reactivated a version of myself that no longer belongs in the present. That person, with all her raw pain and anger, was real, but she was also a part of my past. To keep her alive would have been to deny myself the chance to move forward.

And so, I let go of the book, and I turned my attention to love.

Windows Shining in Light

Today, I am building a life that feels like it’s truly mine. It’s a life guided by my own rhythm, rooted in love, and open to connection. The anger that brought me home has transformed into something more grounded, more enduring.

Even in the shadow of profound harm, love remains. It isn’t just a memory or a distant ideal—it’s a force we can reclaim, an energy that can shape our lives anew. And for me, that has been the greatest gift of all.

Leave a comment